As Special Olympics around the globe celebrate its 50th Anniversary, there’s a distinct and small group of people who can be recognized for their commitment to the movement since Day 1.

Canada’s very own Dr. Frank Hayden is one of those people. It was his research on the impact of fitness and sport on individuals with intellectual disabilities that helped found Special Olympics in 1968.

While his work validated the need for the movement 50 years ago, he stumbled upon his life-changing research by happenstance.

In the early 1960s, after completing his Master of Science in Physical Education at the University of Illinois, Hayden was in search of a job back in Canada.

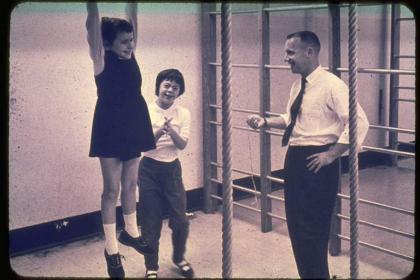

The University of Toronto offered him a research position at the Beverley School, made up of 375 local children with intellectual disabilities.

Having never worked with this population, Hayden did some research before accepting the job.

“I found out there was almost nothing done, so I said, ‘Frank, you’ll be an instant expert – there’s no competition here,’” Hayden recalled. “It was really the blank sheet that attracted me … but the reason I stayed was because I got so energized and excited working with the kids.”

Hayden compared Beverley School students to children without an intellectual disability and found they were “half as fit.” His students carried 35 per cent more body fat, had half the strength and fatigued 40 per cent faster.

He put them through an organized fitness program and within one school year “closed half the gap,” proving their poor fitness level and motor performance wasn’t because of disability – “it was their lifestyle.”

“They arrived at school in taxis, when they got home they just went in the house – nobody in the neighbourhood would play with them,” he said. “If we had a low-active life like theirs’, we probably wouldn’t be any different.”

Hayden presented his findings at an international conference, but didn’t garner any interest.

By 1964, he published a book, complete with sample lesson plans for educators.

It sold 50,000 copies.

His research caught the attention of Canadian broadcaster and long-time advocate for people with an intellectual disability, Harry “Red” Foster - the man who would eventually play an instrumental role in incorporating Special Olympics in Canada.

Hayden and Foster tried to launch a Special Olympics National Games in Toronto, but it never got off the ground.

It wasn’t until 1965, when Hayden received a call from the Kennedy Foundation, that his idea started to gain traction. Eunice Kennedy Shriver, U.S. President John Kennedy’s sister, was running summer camps for individuals with intellectual disabilities and was interested in Hayden’s work.

Hayden moved to Washington, D.C., with his wife Marion and four kids in tow, to work alongside the Kennedy Foundation in organizing the first-ever Special Olympics Games at Soldier Field in Chicago.

On July 20, 1968, athletes from 25 states competed, as well as one Canadian floor hockey team – made up of students from the Beverley School.

Hayden remembers seeing Foster that day.

“He’s red as a beet because of the sun, but the excitement on his face … he saw what was going on and said, ‘Frank, this is fantastic. We should have this in Canada,’” Hayden recalled.

With Foster’s help, the first Special Olympics Games took place in Toronto the following year and Hayden continued to grow the movement in the U.S.

In the late 1980s, Hayden helped launch 50 more Special Olympics organizations around the world, before returning to Special Olympics Canada in 1994.

Now 88-years-old, Hayden is retired, but his passion for the movement is as strong as ever.

Alberta athlete Darby Taylor remembers hearing Hayden speak for the first time at the Special Olympics Canada 2010 Summer Games in London, Ontario.

“(Special Olympics) is very important to me. It’s gotten me out of the house, meeting people,” the 24-year-old bocce player said. “I’m a huge fan of Dr. Hayden.”

Taylor nominated Hayden for induction into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame.

“Most people do not realize that there is a strong Canadian connection to the worldwide organization,” Taylor wrote in his nomination form. “Hayden’s involvement in the creation of Special Olympics … has made an invaluable difference to the lives of those who have intellectual disabilities. I am one of those people and I am very proud to be a Special Olympics athlete.”

Taylor flew to Toronto in 2016 when Hayden was inducted. They still keep in touch.

Whether an athlete competing at the Special Olympics World Games, or a five-year-old attending Active Start at a community centre, Hayden continues to believe “sport is the answer.”

“My idea wasn’t to find the fastest runner with an intellectual disability,” he said. “It was to make them fitter and healthier, so they have the opportunity to live their potential.”

Help Special Olympics Canada continue Hayden's vision for 50 more years by making a donation today.